The first task that any new parent has is to provide their progeny with a name, since the baby cannot be forever known as “The Baby” or “My Baby.” They need names and, as a parent, you may decide to bestow a weighty or whimsical moniker upon your blessed offspring—the kind of thing that, as the child grows up, often feels like an ill-fitting suit at best.

I mean Grandma Esther may have been your favorite Grammy, and when your new daughter was born, naming the child Esther may have seemed like a great way to honor Grammy Esther. However ‘Lil Esther may well decide it’s an awful name, and decide that being Esther is awkward as fu*k as the kids say—and opt to use a nickname or to just rename themselves. Often without ever going through the legal name-changing process.

I was born in the early 1970s, during the era of the Black is Beautiful movement, at a time when many Black folks were exploring their connection to the continent of Africa. Jim Crow had legally ended just a few years prior to my birth year and Black folks were in a state of exploration of self.

As a result, there were many Black kids born in the 1970s who have African-inspired names. Yours truly is no exception. Though I almost ended up with a “standard American” name.

You see, my parents couldn’t agree on a name for me. So, for two weeks, I remained nameless. In fact, my birth certificate does not have a first name listed. Which, with my dad’s passing, means getting a passport to get out of this raggedy country just got exponentially harder—but that’s another story.

The story I was told was that Dad wanted me to have a more traditional American name. But my mother, who was named for a very white and popular blond actress in the 1950s, did not want me to have any name that sounded remotely white. Which is why my given name is not Charlotte as my Dad wanted and is instead Shamika.

Yep, Shay is a childhood nickname. Other childhood nicknames include Meka and a few others that only family and a handful of friends know.

So why do I use Shay professionally? Truthfully, growing up in the ‘70s and ‘80s, people always butchered my name and by my late teens and early 20s, my own internalized racism made me want to distance myself from that name.

However it was around 1995, when I was sending out resumes that I did an experiment—eight years before the National Bureau of Economic Research did a similar thing as an official study—where I started sending out resumes using my nickname and not my given name. And what did I learn quickly? That Shay received a lot more return calls than Shamika. Back in those days. the first contact with a potential employer was by phone, and thanks to having perfected the “white voice,” let’s just say that I landed a lot of interviews. Granted, when I showed up in my full Black glory, some potential employers balked but others were fine. At that point, almost 25 years ago, I started using Shay professionally and publicly. It’s easy to say and easy to spell. I did think about legally changing my name, but decided against it for myriad reasons, including the fact that Shamika is who I am—as is Shay.

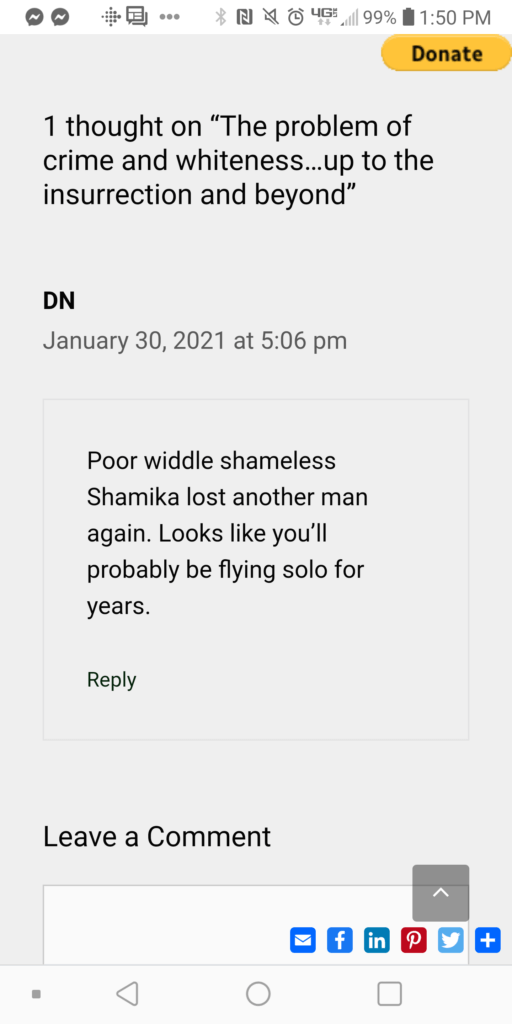

The reason I am sharing this tale is that for over a year now, I have been dealing with an intermittent internet stalker. Someone who last year discovered my legal name and who sends me taunting messages by email and on my blog. This person makes a special note of using my legal name and mocking my personal life—and implied in their messages at times is a “threat” that they will “out” me.

Look, my legal name is a matter of public record. As the executive director of a 501(c)(3) non-profit, our organizational tax records have to be public. So, anyone savvy enough to use Guidestar can pull our tax records and see my legal name since the CEO and all board members have to be listed—and for purposes of the tax man, I use my legal name. And if you have ever made a donation to this site’s Paypal, you get my legal name, too. It’s hardly a secret.

At 48, I no longer am filled with internalized racism or anguish over my given name. Fact is, racial bias is real and racial name bias is even more real. I started my career at a time when the conversations we now have really didn’t exist. I used all the tools at my disposal to get my foot in the door. Many a BIPOC person has used an “American” or, to be real, a “white” name to gain entry to spaces where we have not been easily allowed.

Thankfully, the world is changing and we are moving to a place where young Black people less often have to change their “ethnic”-sounding names to get a job, and I would like to think that the work done by folks like myself and many others has helped to create that change.

I will not be shamed by some anonymous coward who has nothing better to do than to scan all my public social media to try and attack me. I know who I am; do you know who you are?

On another note, there is also a good chance that this Black girl’s made-up, back-to-Africa name will be on a ballot coming soon. If you live in District 1 for Portland, Maine, stand by—more details coming.

If this piece or this blog resonates with you, please consider a one-time “tip” or become a monthly “patron”…this space runs on love and reader support. Want more BGIM? Consider booking me to speak with your group or organization.

Comments will close on this post in 60-90 days; earlier if there are spam attacks or other nonsense.

What do you plan on doing to help progress the City of Portland, Maine.

ISP6083L

Love this! You are keeping it real. I was looking for a link to your amazing podcast tonight (I listened to episode 1 earlier), and happened upon this post. I will definitely be sharing your political aspirations with everyone I know in Maine. (okay that’s 5 people, but that’s a start!)