We all are capable of unintentionally harming people, especially Black and brown people, by lumping them into categories that erase disparities and differences between groups. In some ways the phrases and terminology we use reflect the evolution of scholarship and knowledge about race and ethnicity, but in other ways it is also a matter of expediency and convenience. While certain terms and phrases can reflect shortcomings in how we frame discussions on race and ethnicity in America, once we realize and internalize that those terms and phrases can do more harm than good and blur the lines between discrete groups with disparate experiences—that is when me must demand change from ourselves and from others to use terminology that does justice to the issues we are seeking to address.

While in some cases situational, among the most widely-used contemporary examples of problematic terminology and phrases are “people of color,” “disadvantaged communities,” “communities of color,” and “minorities.”

I say situational because there are limited circumstances in which the terminology above can be used, namely when we are discussing issues broadly or issues that broadly impact numerous discrete groups of people.

For instance, when discussing white supremacy, one could get away with saying that “White supremacists are targeting people and communities of color.”

But it is when we delve into more specific issues, such as police brutality, mass incarceration, COVID-19, immigration, health, etc. that we can cause more harm than good by aggregating Black and brown people into “people of color” and similarly broad terms.

For instance, in the wake of the tragic death of George Floyd and the national dialogue on police brutality, we shouldn’t say that policing policies and police disproportionately and discriminatorily target, arrest, imprison and murder “people of color.” Instead, we should say that policing policies and police disproportionately and discriminatorily target, arrest, imprison and murder Black people.

The difference is that the first statement is the partial truth, while the latter statement is the whole truth.

Yes, policing policies and police disproportionately and discriminately target, arrest, imprison and murder “people of color,” but depending on if you are Black, Asian American or Pacific Islander, Hispanic or Latino, the experiences—while similar—are not the same.

In 2019, for instance, Black people comprised 24% of those killed by police despite making up only 13% of the U.S. population and are 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police than white people, according to the Mapping Police Violence website. If we were to stick to “people of color,” all we would have known was that 54% of those killed by police officers were people of color—ignoring completely that Black people made up nearly 45% of police killings of people of color.

Disparities among communities of color is exactly why, for instance, researchers are using “Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders,” rather than just “Asian Americans.” Even then, the best practice is to further break down data by ethnicity (Hawaiian, Cambodian, Vietnamese, Laos, Hmong, Filipino, etc.).

But there is another reason why “people of color” should only be used in limited circumstances when referring to issues broadly and issues that have broad impact: “People of color” gives the false sense that simply because we are not white we have it figured out when it comes to race. That is simply not the case. As Shay Stewart-Bouley often says, “Just because we’re skinfolk doesn’t mean we’re kinfolk.”

The reason why white supremacy is so pervasive and so ingrained in our culture and society is because white supremacy divides and conquers. It does this (1) by declaring white as supreme in all aspects (beauty, ability, intelligence, etc.), (2) constructing a “hierarchy of whiteness” in which races with lighter skin were better than others (model minority, lighter skin/passing closer to the top, dark skin on the bottom), and (3) pitting non-whites against each other.

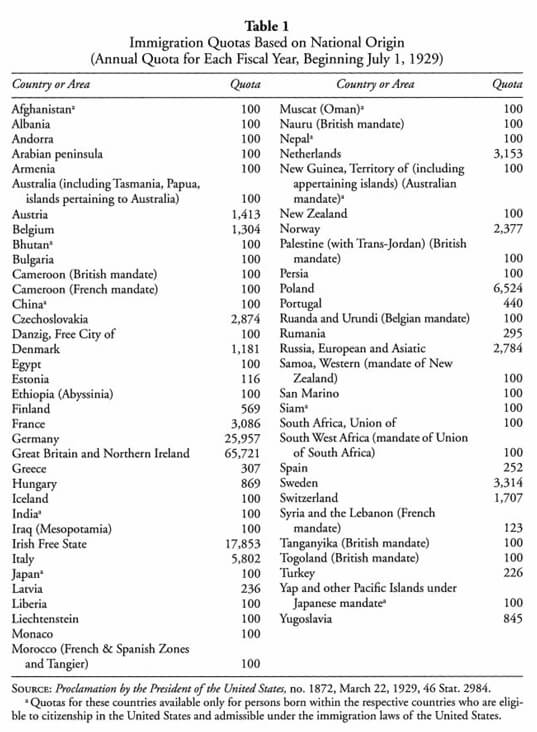

In the “hierarchy of whiteness,” those of Anglo-Saxon and Nordic origins were considered to be the “purest” stock for populating the new American Republic. This was hierarchy was codified in a series of naturalization and immigration laws that imposed racial quotas. The image here is a table representing U.S. racial preferences in the early 1900s.

When I give presentations on immigration, I always ask the audience if any of them have Irish background. Not only because I can relate in a way, having been adopted by white parents with Irish and French Canadian roots, but because Irish folks were not considered white in the 1800s and early 1900s. In fact, my adoptive grandfather used to tell me stories of growing up in Bridgton, Maine, in the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s, and how Irish Catholics were discriminated against by white Protestants.

But over time, Irish Catholics assimilated into whiteness. Especially once John F. Kennedy became America’s first Irish Catholic president. The darker side of this history was that in order to assimilate into whiteness, racism against Blacks was seen as a means to prove their whiteness (check out The Root article When the Irish Weren’t White for more information).

For those of us who are caught in between Black and white, the allure and attraction of whiteness is powerful because it means, in essence, power and privilege. And many who are able to do in fact seek to assimilate into whiteness. Or if they cannot fully assimilate into whiteness, they curry favor by seeking to gain model minority status.

Unfortunately, many brown people (Asian American, Pacific Islander, Latino, etc.) get swept up in the hierarchy of whiteness and model minority status and engage in racism and violence toward blacks. That’s why I was both shocked and not-shocked that an Asian-American police officer stood by while Derek Chauvin knelt on George Floyd’s neck.

As Kimmy Yam writes in the NBC News:

“People don’t have a baseline of an understanding of what anti-blackness even is,” Vaj, who’s Hmong American, said. “Yes, we [Asian Americans] have pain and we suffer from oppression and discrimination and racism. Black people are in a different boat. On top of that, their struggle with the police, at least in this country, has a long history of 400 years of control and occupation. I think that that’s really important for us to acknowledge that.”

Tensions between the black and the Asian communities have long existed. The strained relations stem, in part, from being set in opposition to each other throughout American history, Vaj said.

In another instance in Chicago, non-black, Latino gang members offered the police assistance to help deter protestors.

While not an indictment on all Asian and Latin Americans, it does highlight the pervasiveness of the hierarchy of whiteness and model minority status. Asian American and Pacific Islander and Latino people need to recognize how we are pitted again Black people and used to perpetuate white supremacy in America. We must do the hard work of learning our history, of rejecting and dismantling white supremacy, and standing by our Black brothers and sisters.

That is why we must be careful in using the phrase “people of color” and similar terminology. We cannot make the assumption that all people of color get the anti-racist work we are trying to do here in dismantling white supremacy. I myself as a Cambodian American adopted by white parents had to dismantle my own internalized racism and dispel the myth of the model minority status in order to fully see the rot of white supremacy throughout our society and our communities.

The very same reason why we opt to say “Black Lives Matter,” rather than “All Lives Matter,” applies when we talk about the differences and relationships between Black and brown people. We cannot turn a blind eye to how black and brown people themselves perpetuate white supremacy.

That is why if we are to do justice for all the Black lives lost, especially for brown and white allies, than we must not only speak truth to power—we must speak the whole truth to power. And sometimes the truth does hurt but it is the truth and nothing but the truth that will set us free.

Marpheen Chann is an openly gay, second-generation Cambodian American and a Portland, Maine-based thinker, writer and speaker on LGBTQ+ and immigrants’ rights, social justice and equality. He was born in California to a refugee family who later moved to Maine in the late-90s. At the age of 9, he was placed in foster care and later adopted at age 14 by an evangelical, white working class family in Western Maine. Marpheen is the president of the Cambodian Community Association and has served on the boards of the Greater Portland Immigrant Welcome Center and Maine Association of New Americans. While in law school, he chaired the Maine Law LGBTQ+ Law and Policy group and spent 7 months in the Office of Minority and Women Inclusion at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Marpheen holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Southern Maine and a law degree from the University of Maine School of Law.

If this piece or this blog resonates with you, please consider a one-time “tip” or become a monthly “patron”…this space runs on love and reader support. Want more BGIM? Consider booking me to speak with your group or organization.

Comments will close on this post in 60-90 days; earlier if there are spam attacks or other nonsense.

Excellent. Just an observation or two. Now living in a predominant Hispanic community on Boston’s, North Shore, I am sadden when I hear from school teachers, that their young Hispanic students with African heritage, “hate” this heritage. And when living in Hartford, CT , I saw a clear hierarchy of those with an African heritage. Afro- Caribbean – particularly Jamaican- on the top, and African Americans on the bottom ladder. I think the common factor is that in the process of being Americanized you have to buy into – consciously or not – the Racism that has bloodied American soil since the first Africans were enslaved here at Jamestown, in 1619. This regardless of a shared, “dark hue”.